A Trip to the Heart of Morocco

It all began when my lady and I got off our flight from Cleveland via Cincinnati at JFK. We had to walk outdoors between the domestic terminal and the international terminal to check in for our Royal Air Maroc flight to Casablanca. Previously, Royal Air Maroc informed us over the phone that our seats were secured. In reality, we found at check-in that they weren’t yet assigned, so we ended up with seats not next to each other. Once we boarded, the attractive Moroccan flight attendant informed the guy assigned to sit next to my lady that he and I were switching seats (how could he say no to a Moroccan hottie?). Other than our seats being right across from the toilet and un-reclinable, the flight was uneventful.

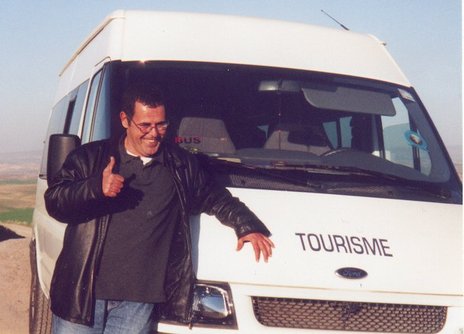

We arrived at Casablanca and were greeted by our guide, Mohammed Masrour. We were the only couple for the 10-day adventure (not counting the 2 travel days). This opened many doors for us and immediately immersed us in the culture. We weren’t with a large tour group for locals to scoff. We didn’t have to worry about what 10 other people wanted to see or do (or rely on any itinerary). We didn’t have to make small-talk with a bunch of other Americans. All of our interactions were with real Moroccans, and interacting was definitely interesting.

We arrived at Casablanca and were greeted by our guide, Mohammed Masrour. We were the only couple for the 10-day adventure (not counting the 2 travel days). This opened many doors for us and immediately immersed us in the culture. We weren’t with a large tour group for locals to scoff. We didn’t have to worry about what 10 other people wanted to see or do (or rely on any itinerary). We didn’t have to make small-talk with a bunch of other Americans. All of our interactions were with real Moroccans, and interacting was definitely interesting.

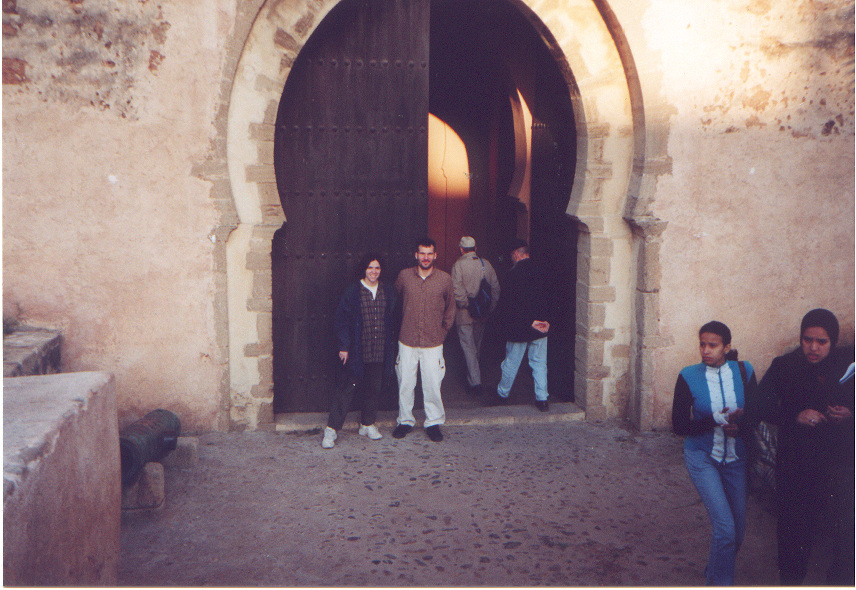

Mohammed drove us to our hotel in Rabat, where we were able to take a short nap to help the jet-lag, after which we had lunch at the hotel. In the late afternoon (lunch is around 2 in Morocco), we did the requisite site seeing in the current capital city. You see, every time the country gets a new king, the capital could conceivably change, and it has in the past. We walked through the Kasbah (old military fortress/castle) then had our first mint tea at the edge of the medina overlooking the sea. The medina (in English, pronounced ma-deena) is a maze of narrow streets wide enough for a donkey or two, but not for a car. It is lined by merchants and their living quarters. The tea included fresh mint.

The next day, we stopped at Alarbiaa, which had the souk on Thursday. The souk is a traveling flea-market that goes from town to town selling all kinds of cheap (both in price and quality) goods. I bought a short wave radio. The first one didn’t work so I had to exchange it for another one on which the volume control became flaky within a week. We passed stuff like kif pipes, grill racks, and fake Michael Jordan shoes. It was PACKED with people, and we found the whole souk concept to be a bit ridiculous. We were told to watch our wallets, and my lady actually felt someone put their hand in her coat pocket in a failed attempt to pick it.

For lunch, we ended up at the Motel Rif, just outside of Ouazane (pronounced “WaaZaa”). We had Tagine Chicken. A tagine is a shallow ceramic bowl with a ceramic lid. The food is cooked inside. The lid is then removed and voila, lunch is served. It was pretty good, the first authentic Moroccan meal of many that were to come. We met this one cat that worked there named Khalid. In Arabic, the Kh is pronounced kind of like a “hard HHHH” with the middle of your tongue practically touching the top of your mouth.

The next day, we stopped at Alarbiaa, which had the souk on Thursday. The souk is a traveling flea-market that goes from town to town selling all kinds of cheap (both in price and quality) goods. I bought a short wave radio. The first one didn’t work so I had to exchange it for another one on which the volume control became flaky within a week. We passed stuff like kif pipes, grill racks, and fake Michael Jordan shoes. It was PACKED with people, and we found the whole souk concept to be a bit ridiculous. We were told to watch our wallets, and my lady actually felt someone put their hand in her coat pocket in a failed attempt to pick it.

For lunch, we ended up at the Motel Rif, just outside of Ouazane (pronounced “WaaZaa”). We had Tagine Chicken. A tagine is a shallow ceramic bowl with a ceramic lid. The food is cooked inside. The lid is then removed and voila, lunch is served. It was pretty good, the first authentic Moroccan meal of many that were to come. We met this one cat that worked there named Khalid. In Arabic, the Kh is pronounced kind of like a “hard HHHH” with the middle of your tongue practically touching the top of your mouth.

I started talking with Khalid (through translation). I’d read the stories about Morocco’s relationship with the cannabis plant. Being in Morocco, it was decided to check the stories. The cannabis plant is known as the kif plant in Morocco. Kif is a French word that, in English, is pronounced “keef.” The plant is shaken, and off of the buds comes the kif, or cannibis. In the US, the word “kif” is used to describe the powder that falls from the buds when they are run back and forth over a screen. In Morocco, they pack that powder together and get scheet, or hashish. After the hashish is extracted, they may cut the left over kif with tobacco and sell it (as kif). The scheet is sold separately and is subsequently rolled into a rolling paper with tobacco extracted from a cigarette (non-Muslim Moroccans like Marlboros, but on the bottom of every box is a warning in Arabic that says “Don’t smoke, it’s bad for you”).

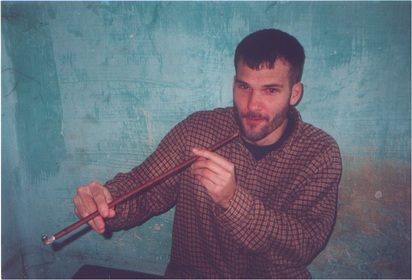

Determined to find out more about the legend, Khalid took us to his hometown of Ouazane into the hills of the medina. We ended up near the top and walked into a small coffee shop (I mean, really small) on the 2nd floor. Inside, the owner was brewing some mint tea in a small corner, an old man was drinking some at a small table, and a kid was sitting at the threshold of the door to the balcony puffing on a scheet-lined cigarette. Khalid sent the kid on a mission, and he returned with a small bag of kif. It was the first I’d seen of the legend, and we packed some into a long, skinny wooden pipe with a small ceramic bowl (common in Morocco). I took a puff and I was immediately put into a state that I found intense, but a bit strange. Then, there was a mellow pot buzz for a short while.

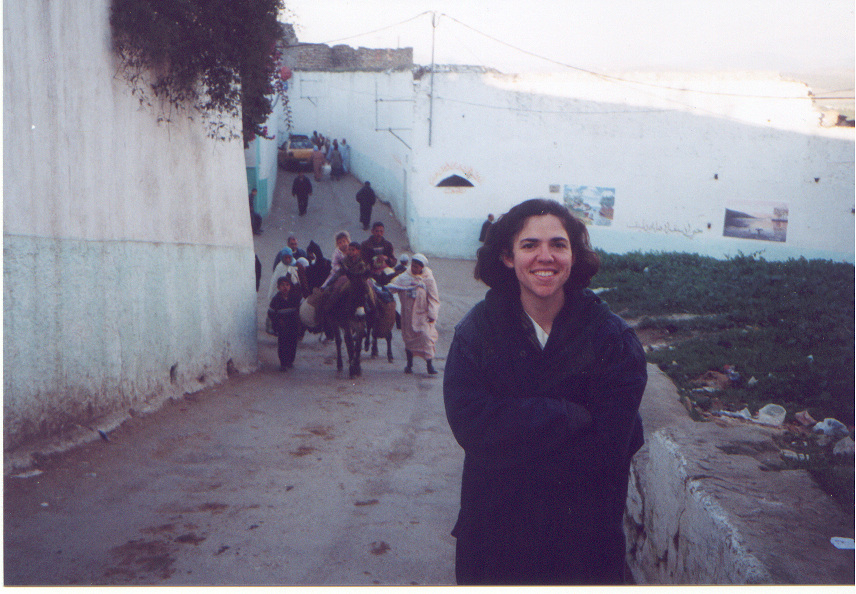

We sat on the balcony sipping tea as the hustle and bustle of daily life went on below. Children playing football in the street, men guiding their loaded donkeys through the people; women carrying toddlers on their backs, and human push carts everywhere; it was Morocco. We descended into the medina for a short tour.

Unlike in the big cities, in the small towns, most of the women wore head scarves. The shrines and coffee shops were only for the men. As my lady accompanied us everywhere (including into the coffee shops), she seemed like a black kid in white bred suburban America. However, the children loved her. They would shout “Bonjour! Bonjour Madam!” in an attempt to elicit a response. It was as if the children reveled in what she represented, a free woman not bogged down by the impositions of men, just like themselves as children (for now).

Determined to find out more about the legend, Khalid took us to his hometown of Ouazane into the hills of the medina. We ended up near the top and walked into a small coffee shop (I mean, really small) on the 2nd floor. Inside, the owner was brewing some mint tea in a small corner, an old man was drinking some at a small table, and a kid was sitting at the threshold of the door to the balcony puffing on a scheet-lined cigarette. Khalid sent the kid on a mission, and he returned with a small bag of kif. It was the first I’d seen of the legend, and we packed some into a long, skinny wooden pipe with a small ceramic bowl (common in Morocco). I took a puff and I was immediately put into a state that I found intense, but a bit strange. Then, there was a mellow pot buzz for a short while.

We sat on the balcony sipping tea as the hustle and bustle of daily life went on below. Children playing football in the street, men guiding their loaded donkeys through the people; women carrying toddlers on their backs, and human push carts everywhere; it was Morocco. We descended into the medina for a short tour.

Unlike in the big cities, in the small towns, most of the women wore head scarves. The shrines and coffee shops were only for the men. As my lady accompanied us everywhere (including into the coffee shops), she seemed like a black kid in white bred suburban America. However, the children loved her. They would shout “Bonjour! Bonjour Madam!” in an attempt to elicit a response. It was as if the children reveled in what she represented, a free woman not bogged down by the impositions of men, just like themselves as children (for now).

We ended up in another coffee shop. There was a bunch of old dudes in one corner playing cards. In the other, a bunch of younger dudes were watching a low budget Spaghetti Western with American actors and Arabic subtitles. Due to the multitude of languages, it was not uncommon to see American films in English with Arabic or French subtitles, French movies with French subtitles (so the Moroccans could brush-up), or Arabic movies with English or French subtitles (along with movies filmed in one language, but dubbed in another). The radio was another story, with songs having English, French, and Arabic lyrics (sometimes, even in the same song).

Khalid elicited two dudes from the other table to partake in a small kif smoking (it was common in the coffee shops, except in the big city where the cops hang out). One guy spoke decent English, and we assumed it was from the westerns. He rolled up a traditional scheet-lined tobacco cigarette and it was passed around, skipping those uninterested (like myself, naturally). The other guy whipped out some sort of substance that was later described to me (in French) as basically schit made from tobacco. He snorted it and offered me some. Khalid made the international sign for “crazy,” so I decided it was a bad idea.

In Morocco, they generally speak Arabic and French. However, they actually have a language of their own consisting of Arabic words, French words, and Berber words. The Moroccan language varies from town to town, but somehow everyone understands each other. My lady muddled through with a little French from what she’d learned in high school, but I had to rely on her and Mohammed to communicate. Though, the next day we did meet a man Mohammed called “the smart man” in the small town of Amerguou that was way more up on American politics than most Americans are. Among his modest set of English words was “Condoleezza Rice,” as her Senate confirmation was the primary political story of the day. We continued on to Taza to spend the next few days with Mohammed’s cousins.

It was at this time that we really realized how fortunate we were. We spent three nights in Taza with a family consisting of Abdou, an olive-oil producer, his brother Rachid’s family, their sister (a practicing Muslim that was kind enough to find me an English Qur’an), and the cook Hakima (and what a cook she was!).

Khalid elicited two dudes from the other table to partake in a small kif smoking (it was common in the coffee shops, except in the big city where the cops hang out). One guy spoke decent English, and we assumed it was from the westerns. He rolled up a traditional scheet-lined tobacco cigarette and it was passed around, skipping those uninterested (like myself, naturally). The other guy whipped out some sort of substance that was later described to me (in French) as basically schit made from tobacco. He snorted it and offered me some. Khalid made the international sign for “crazy,” so I decided it was a bad idea.

In Morocco, they generally speak Arabic and French. However, they actually have a language of their own consisting of Arabic words, French words, and Berber words. The Moroccan language varies from town to town, but somehow everyone understands each other. My lady muddled through with a little French from what she’d learned in high school, but I had to rely on her and Mohammed to communicate. Though, the next day we did meet a man Mohammed called “the smart man” in the small town of Amerguou that was way more up on American politics than most Americans are. Among his modest set of English words was “Condoleezza Rice,” as her Senate confirmation was the primary political story of the day. We continued on to Taza to spend the next few days with Mohammed’s cousins.

It was at this time that we really realized how fortunate we were. We spent three nights in Taza with a family consisting of Abdou, an olive-oil producer, his brother Rachid’s family, their sister (a practicing Muslim that was kind enough to find me an English Qur’an), and the cook Hakima (and what a cook she was!).

Immediately, many rumors about Morocco were dispelled. Not everyone is a non-drinking Muslim that prays 5 times a day. Most of the people we’d met were like the average person in America that is not fervent about any particular religion, but loosely follows traditions (like Christmas in America). However, there are many devout Muslims. From every mosque you will hear a minister calling out over loudspeakers 5 times per day as a reminder to pray. You can even hear the reminders from the most remote areas of the country, because they are coming from all directions as there are many mosques in Morocco. Also, many people (Abdou’s sister and Mohammed’s wife, to name but two) are anti-drinking and feel strongly about following the righteous path to the holy land. However, this is not everyone. As an example, I think that Rachid could drink me under the table any day of the week. Nevertheless, of course, it is not a way of life. We had a few beers together (bridged by a day of complete abstinence for all but Mohammed & Abdou’s terrible cigarette habit); however, they never drink around non-drinking family out of respect and courtesy.

Respect and courtesy runs very deep in Moroccan culture. When we stayed with Abdou, my lady and I slept in his bed as he slept on the couch (this was similar when we later stayed with Mohammed, as he and his wife gave us their bed for a night). Another example was the fact that, though they normally spoke Moroccan Arabic in conversation, Abdou started speaking French in an effort to allow my lady into the conversation.

Sometimes, the courtesy even gets annoying (if you can believe it). One of the themes of the trip was the constant “You must ate! You must ate!” said to us by the men. They were saying “you must eat” but it sounded like “you must ate” due to the accent. We were guests, and they wanted to make sure that we were eating enough. It ended up that this was a good thing, because we were never hungry and we really needed the nourishment not only for the physical activity, but also the mental activity of trying to assimilate with this completely different world. Fortunately, when we ate with the ladies, they were generally far too courteous to issue such commands (though they would on the sly slide more food to us out of the collective plate).

In Morocco, everyone eats from a single large communal plate (or tagine bowl). They take pieces of bread and grab chunks of food from the plate with their hands and eat it. One night, my lady and I were picking at the shared chicken with forks and the niece of Abdou was perplexed at this custom. We then just started ripping it away from the bone with our hands to fit in.

Respect and courtesy runs very deep in Moroccan culture. When we stayed with Abdou, my lady and I slept in his bed as he slept on the couch (this was similar when we later stayed with Mohammed, as he and his wife gave us their bed for a night). Another example was the fact that, though they normally spoke Moroccan Arabic in conversation, Abdou started speaking French in an effort to allow my lady into the conversation.

Sometimes, the courtesy even gets annoying (if you can believe it). One of the themes of the trip was the constant “You must ate! You must ate!” said to us by the men. They were saying “you must eat” but it sounded like “you must ate” due to the accent. We were guests, and they wanted to make sure that we were eating enough. It ended up that this was a good thing, because we were never hungry and we really needed the nourishment not only for the physical activity, but also the mental activity of trying to assimilate with this completely different world. Fortunately, when we ate with the ladies, they were generally far too courteous to issue such commands (though they would on the sly slide more food to us out of the collective plate).

In Morocco, everyone eats from a single large communal plate (or tagine bowl). They take pieces of bread and grab chunks of food from the plate with their hands and eat it. One night, my lady and I were picking at the shared chicken with forks and the niece of Abdou was perplexed at this custom. We then just started ripping it away from the bone with our hands to fit in.

In Taza, I met some friends. One tried the kif from Ouazane and immediately noticed that it was very tobacco heavy. I then realized that it was a tobacco buzz at the coffee shop that felt so strange (I don’t smoke cigarettes). I told them about the custom that Americans do not mix their kif with tobacco. They told me of a professor they once knew from America that smoked his scheet directly from a Moroccan pipe (the one with the small ceramic elbow). We hooked up with some uncut kif for scientific comparison to the cut stuff. Also, we acquired a small quantity of the renowned Moroccan schit. For a local, the price of kif and scheet is minute.

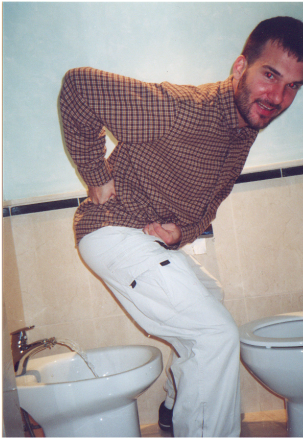

It was under the influence of the schit that I put some serious thought into the customs of taking a shit in Morocco. At the hotels were bidets. According to American Heritage dictionary, a bidet is “a fixture similar in design to a toilet that is straddled for bathing the genitals and the posterior parts.” In Morocco, toilet paper is less common. It is felt that water gets you much cleaner after taking a dump than TP.

It was under the influence of the schit that I put some serious thought into the customs of taking a shit in Morocco. At the hotels were bidets. According to American Heritage dictionary, a bidet is “a fixture similar in design to a toilet that is straddled for bathing the genitals and the posterior parts.” In Morocco, toilet paper is less common. It is felt that water gets you much cleaner after taking a dump than TP.

|

The house at which we stayed in Taza was built in the early 70’s and was outfitted not with toilets and bidets, but Turkish baths. A Turkish bath is a ceramic fixture as well, but in the floor at the edge of the room. It is about a square-yard and has two elevated areas for your feet. In between the feet steps and the wall is a single hole. You can stand on the foot steps facing the wall and piss into the hole. Alternatively, you can place your feet on them with your back to the wall and squat. Your asshole is then aimed at the small hole into which you shit. I told Mohammed that I was proud of my first use of the Turkish Bath because I got the shit in the hole. He called me “the sniper.”

When finished shitting, a bucket is awaiting under a spigot in the wall. You turn the water on to fill the bucket (as you take the appropriate water to wipe your ass). You then dump the bucket of water into the hole of the Turkish Bath to flush. Fortunately, we had biodegradable toilet paper. However, the water thing is probably good, considering that most Moroccans don’t shower every day. |

My name, Russ, is also a word in Arabic. It is pronounced “Russ” but translates to “Head.” It was quite interesting when Mohammed would call me in public and people would do a double-take. In Arabic, the letters are read from right-to-left instead of left-to-right. This means that you start reading a book from the back cover to the front cover.

The language barrier was interesting. As we stood at a mountain top that had some snow on the ground, I spent several minutes trying to explain through many hand gestures and simple words that we got over 14 inches of snow in Cleveland last month (never mind that they use the metric system). Also, I was intrigued by the different ways that one moves their tongue and throat in different languages (having English, Arabic, Berber, and French to compare). I noticed it was kind of like playing the saxophone. Mohammed began calling me the “Copperman” (French for “saxophonist”).

In the van, Mohammed, Abdou, and Rachid would have conversations in Arabic that my lady and I could not understand. At the same time, we had conversation in English (with the usual slang) that they could not really comprehend. Perhaps Mohammed could pull out some words here or there, so we tested him by having him recite words sung on the radio. He’d say something that sounded similar, but was totally wrong. It was amusing. They told us that they took the words of the song “Give a little bit… Give a little bit of your love to me…” and put together an Arabic version that went “Gib Albaid Li Flibit” which translates to “Bring Eggs to the Room.”

We went to a cave outside of Taza for a tour. We’d been at a cave outside of San Antonio and the setup was in stark contrast. Unlike San Antonio, the cave in the Middle Atlas had no lights, no helmets issued, no fee, and it was pretty tough to get through. However, our hired guide was a lifesaver (especially for my lady). Also, nobody told you what you couldn’t touch. Besides finding structures that could be hit like hand drums, sometimes there was no other way to get through than to hang on so you didn’t fall. They said “watch your Russ” a lot.

We spent a few days in town exploring the sites of Taza. The internet café is only about 3 Dirham (34 US cents) per half-hour. Single cigarettes are sold on the street everywhere. People buy them from each other (instead of bumming them). Trade often occurs, with folks handing each other a couple Dirhams here or there for cigs, palms, oil, nuts, whatever.

The language barrier was interesting. As we stood at a mountain top that had some snow on the ground, I spent several minutes trying to explain through many hand gestures and simple words that we got over 14 inches of snow in Cleveland last month (never mind that they use the metric system). Also, I was intrigued by the different ways that one moves their tongue and throat in different languages (having English, Arabic, Berber, and French to compare). I noticed it was kind of like playing the saxophone. Mohammed began calling me the “Copperman” (French for “saxophonist”).

In the van, Mohammed, Abdou, and Rachid would have conversations in Arabic that my lady and I could not understand. At the same time, we had conversation in English (with the usual slang) that they could not really comprehend. Perhaps Mohammed could pull out some words here or there, so we tested him by having him recite words sung on the radio. He’d say something that sounded similar, but was totally wrong. It was amusing. They told us that they took the words of the song “Give a little bit… Give a little bit of your love to me…” and put together an Arabic version that went “Gib Albaid Li Flibit” which translates to “Bring Eggs to the Room.”

We went to a cave outside of Taza for a tour. We’d been at a cave outside of San Antonio and the setup was in stark contrast. Unlike San Antonio, the cave in the Middle Atlas had no lights, no helmets issued, no fee, and it was pretty tough to get through. However, our hired guide was a lifesaver (especially for my lady). Also, nobody told you what you couldn’t touch. Besides finding structures that could be hit like hand drums, sometimes there was no other way to get through than to hang on so you didn’t fall. They said “watch your Russ” a lot.

We spent a few days in town exploring the sites of Taza. The internet café is only about 3 Dirham (34 US cents) per half-hour. Single cigarettes are sold on the street everywhere. People buy them from each other (instead of bumming them). Trade often occurs, with folks handing each other a couple Dirhams here or there for cigs, palms, oil, nuts, whatever.

Abdou took us to his olive grove where they made the oil. We saw the huge stone contraptions used to crush the olives into oil. My girl and I took turns riding a donkey through the groves, down to the water, and next to the neighboring tribe. We ended up at the donkey owner’s house for lunch. We were all now guests in this family’s house. He served up the tea. My lady counted 11 tea kettles in that room alone. In Morocco, tea is big. They boil the water in one tea kettle and place the dried leaves in an illustrious serving teapot. Inside, the tea is washed with the hot water a few times. Then, the hot water is poured into the tea, along with heaping helpings of sugar. It is then reheated, and when returned from the heat, methods are employed to cool it to drinking temperature. It is poured from the spout a decent distance into an small glass. If it is still too hot, the tea is poured between different glasses and/or back into the tea kettle. Once it is served, it is still pretty hot. Unlike tea cups, on the glass, there is no handle, so you must put a finger on the rim and another on the bottom corner of the glass to hold it without burning your hand. For lunch, we ate well with a notable dish being a cold soup made from goat milk and milled corn (that went along with the homemade bread and butter). It was another authentic, filling, and delicious lunch.

After observing daily life and being treated like family in Taza for a few days, the three of us went camping with Abdou and Rachid. The campsite was a very remote area in Eastern Morocco (about 100km from Algeria). Morocco has two deserts, the Desert of the Sand (the Sahara), and the Desert of the Stone (kind of like Aruba). Where we were, it looked like Mars, but with water. A dam was built nearby, causing a large lake. The eye candy of the landscape, water, and vastness was breathtaking. We built a fire and ate freshly grilled sardines, chicken, and mincemeat kebabs for dinner.

The next day, we drove through many small towns on the way to Fes, Mohammed’s home town (though he grew up in Taza). In one of the small towns on the way, we got 2 teas and a cappuccino for a total cost of a whopping 6 Dirham (65 US cents). Mohammed was uncertain about the cleanliness of the food on the way so we picked up some bread, cheese, sardines, and coca-cola (with Arabic lettering) for us to eat at lunch. We had a picnic at an overlook and took a short hike up a big hill. Again, the views of the day were fantastic.

We ended up at the hotel in Fes. My lady and I had some quality time before we awoke the next day for the American dream: shopping. Let me first say that I generally can’t stand shopping. However, we had a list. We met our guide for the Fes Medina Shopping Spree at the hotel. His name was Salim. His credo seemed to be to find us quality. He grew up in Fes and knew most of the old-school merchants. First on our list was a tagine. We ended up at a ceramics place that was a school for ceramics, having all the equipment and talent on-site. We picked up the tagine, along with a gift for a family member at home.

Next on our list was a tea kettle. Salim took us to a place that gave us a full demonstration about their quality. The artist for the engraving was sitting there working on a piece. He used an awl with a single point on it. The owner showed us that cheaper versions used awls that had templates (of a star or line, for example). We picked up a sweet serving tea kettle along with a serving tray. Also, we got a bronze tray to hang on the wall as a gift.

The prices started adding up quickly. Next up was the carpet store. Mohammed had previously praised Moroccan carpets. We weren’t really planning on it. We ended up walking out with some really nice sheep wool carpets (they are so soft in front of our bed), along with an elaborate runner that is reversible (summer and winter). We had a real salesman on our hands, but my lady and I walked away happy (and I couldn’t help thinking they did as well). Negotiating was quite a process.

Next, Salim took us to a tannery. Outside, you could see about a hundred different pits filled with various colors and used to dye the hides used to make leather. We got a foot-stool for a gift. Finally, I hooked up with a jalaba. These outfits are worn all over the North by the local men. A brown one with a hood is kind of like Obi Wan’s robe, but it doesn’t split all the way down in front. A white hooded jalaba vaguely resembles KKK garb. I also hooked up with a ceramic darbuka, which is a conga-like drum shaped like an hour-glass. Before we even got to the place that made the fancy knit-design table cloths (which can only be sewed by ambidextrous knitters), we were broke. However, if you’re rich (or really dig debt), I’m sure you could go all out for days. It’s all good because it helps the local economy.

The next day, we went to the small village of Bhalil to visit a family that lived in a cave for tea. It was another one of the many small jewels we’d encountered during our travels. After this, we went home and ate couscous with Mohammed’s family. That evening, we ate many fantastic sweets prepared by the wife of Mohammed. Mohammed and I ran a small errand to the store as my lady observed Mohammed’s wife spend over four hours cooking a dazzling dinner for all.

The next day, Mohammed was going to be sleeping in the van on the beach while my lady and I slept at the hotel in Casablanca, so he needed some beers. The beer stores would be closed then for the Eid Al-Adha festival, so Mohammed and I walked to the local supermarket to grab a couple bottles while the cooking extravaganza was in progress. The store was packed with many men (no women in sight) all standing in a swiftly-moving line eager to get their beer for the holiday. The lines moved quickly. It was organized chaos. As I purchased my beer, the guy at the counter told me in French to give him two more Dirham to make even change. I sheepishly looked at him as I had no idea what he was saying.

That night, we watched a little Moroccan satellite TV, nestled with the sweetest old Berber lady you could ever imagine, Mohammed’s mom. She had a tattoo on her chin that signified her tribe, and she was now almost completely blind from diabetes complications. It was a pleasure to guide her across the room and to her seat where she beckoned us with the only French she knew, “Mangez! Mangez!” (Eat! Eat!).

After observing daily life and being treated like family in Taza for a few days, the three of us went camping with Abdou and Rachid. The campsite was a very remote area in Eastern Morocco (about 100km from Algeria). Morocco has two deserts, the Desert of the Sand (the Sahara), and the Desert of the Stone (kind of like Aruba). Where we were, it looked like Mars, but with water. A dam was built nearby, causing a large lake. The eye candy of the landscape, water, and vastness was breathtaking. We built a fire and ate freshly grilled sardines, chicken, and mincemeat kebabs for dinner.

The next day, we drove through many small towns on the way to Fes, Mohammed’s home town (though he grew up in Taza). In one of the small towns on the way, we got 2 teas and a cappuccino for a total cost of a whopping 6 Dirham (65 US cents). Mohammed was uncertain about the cleanliness of the food on the way so we picked up some bread, cheese, sardines, and coca-cola (with Arabic lettering) for us to eat at lunch. We had a picnic at an overlook and took a short hike up a big hill. Again, the views of the day were fantastic.

We ended up at the hotel in Fes. My lady and I had some quality time before we awoke the next day for the American dream: shopping. Let me first say that I generally can’t stand shopping. However, we had a list. We met our guide for the Fes Medina Shopping Spree at the hotel. His name was Salim. His credo seemed to be to find us quality. He grew up in Fes and knew most of the old-school merchants. First on our list was a tagine. We ended up at a ceramics place that was a school for ceramics, having all the equipment and talent on-site. We picked up the tagine, along with a gift for a family member at home.

Next on our list was a tea kettle. Salim took us to a place that gave us a full demonstration about their quality. The artist for the engraving was sitting there working on a piece. He used an awl with a single point on it. The owner showed us that cheaper versions used awls that had templates (of a star or line, for example). We picked up a sweet serving tea kettle along with a serving tray. Also, we got a bronze tray to hang on the wall as a gift.

The prices started adding up quickly. Next up was the carpet store. Mohammed had previously praised Moroccan carpets. We weren’t really planning on it. We ended up walking out with some really nice sheep wool carpets (they are so soft in front of our bed), along with an elaborate runner that is reversible (summer and winter). We had a real salesman on our hands, but my lady and I walked away happy (and I couldn’t help thinking they did as well). Negotiating was quite a process.

Next, Salim took us to a tannery. Outside, you could see about a hundred different pits filled with various colors and used to dye the hides used to make leather. We got a foot-stool for a gift. Finally, I hooked up with a jalaba. These outfits are worn all over the North by the local men. A brown one with a hood is kind of like Obi Wan’s robe, but it doesn’t split all the way down in front. A white hooded jalaba vaguely resembles KKK garb. I also hooked up with a ceramic darbuka, which is a conga-like drum shaped like an hour-glass. Before we even got to the place that made the fancy knit-design table cloths (which can only be sewed by ambidextrous knitters), we were broke. However, if you’re rich (or really dig debt), I’m sure you could go all out for days. It’s all good because it helps the local economy.

The next day, we went to the small village of Bhalil to visit a family that lived in a cave for tea. It was another one of the many small jewels we’d encountered during our travels. After this, we went home and ate couscous with Mohammed’s family. That evening, we ate many fantastic sweets prepared by the wife of Mohammed. Mohammed and I ran a small errand to the store as my lady observed Mohammed’s wife spend over four hours cooking a dazzling dinner for all.

The next day, Mohammed was going to be sleeping in the van on the beach while my lady and I slept at the hotel in Casablanca, so he needed some beers. The beer stores would be closed then for the Eid Al-Adha festival, so Mohammed and I walked to the local supermarket to grab a couple bottles while the cooking extravaganza was in progress. The store was packed with many men (no women in sight) all standing in a swiftly-moving line eager to get their beer for the holiday. The lines moved quickly. It was organized chaos. As I purchased my beer, the guy at the counter told me in French to give him two more Dirham to make even change. I sheepishly looked at him as I had no idea what he was saying.

That night, we watched a little Moroccan satellite TV, nestled with the sweetest old Berber lady you could ever imagine, Mohammed’s mom. She had a tattoo on her chin that signified her tribe, and she was now almost completely blind from diabetes complications. It was a pleasure to guide her across the room and to her seat where she beckoned us with the only French she knew, “Mangez! Mangez!” (Eat! Eat!).

Throughout the week, as men bought sheep all across the country at huge sheep-selling events, we learned that our last full day was going to be the Eid Al-Adha festival. This is a Muslim festival that comes from a story in the Qur’an about Abraham, who took his son to sacrifice in the name of Allah. Allah gave him a sheep instead so he could save his son. To celebrate, families all buy their own sheep and have it sacrificed on their rooftop. We were lucky enough to witness it with Mohammed’s family.

Like many other Muslims that day, Mohammed brought home his sheep Friday morning and tied it up on his roof top (which, like many Moroccan houses, was an open floor atop the house having walls but no ceiling. Like the other sheep we’d seen, Mohammed’s was stubborn. Eventually the butcher showed up.

Mohammed and the butcher held the sheep down while the butcher made one swift slice through the neck, cutting open the windpipe and severing the two carotid arteries, which continued to pump blood from the body as the sheep fell to the ground and exhaled its last breath through its open neck. The head was removed and the body hung as the blood flowed from the severed arteries. The hide was slid from the body like pulling off a tight shirt, and the chest opened. The stomach was carefully detached and dropped to the floor so as not to damage the meat. The organs were put on a tray, along with some fat. Since the meat needed to be aged for a few more days, this was a day for eating organs and heads. Mohammed’s wife and her sister prepared some liver which was boiled then wrapped in fat and grilled on skewers. We tried some, but fortunately, we didn’t hear “you have to ate!” at that point. We walked the streets and saw people grilling sheep heads on open fires in celebration. Soon the children would be selling heads to make a few Dirham.

After this second climax of the trip, we drove to Casablanca, via the ancient Roman city of Volubulus, where we saw our first tour bus. We again counted our lucky stars that we picked the right tour, as we saw the fat oozing from this lady’s spandex. We were then off to Casablanca, where we spent a night at a hotel on the shore where we had dinner.

The hotel food had nothing on the home cookin’. We were so fortunate to be able to eat like real Moroccans. We woke up the following morning and snapped a few pictures at the large mosque in town. We were then escorted to the departure point by our guide after a near-teary goodbye.

Our flight back was uneventful (with better seats) until we hit the states. It turned out that the first major snowstorm of 2005 was brewing below us. Of course, we were left in the dark from the crew except that the weather was bad below, so we were going to circle for a while. On the way back, there was no movie on the screen, only the flight trajectory. We saw the plane circle the north-end of Long Island, followed by a circle at JFK. We were then informed that there was an “emergency landing” at JFK (euphemism for “a plane slid off the runway”), and that we were being diverted to Newark.

We landed in Newark and eventually got through customs there. I knew that nobody would be watching out for us and decided that our best option at that time was a drive back to Cleveland. Our flight from JFK to Cincinnati was cancelled, and the next one was not to leave JFK until the following day at 3pm. Due to the weather, the monorail was out of commission, so we waked with our luggage about a half-mile through foot-deep snow to Hertz. We hooked up with a Toyota Camry and I drove through the conditions until I couldn’t drive any more (this was about one hour, putting us just off of I-280 in Jersey at a Residence Inn). It was about 2:30 am Morocco time by the time I got to bed at 9:30. Fortunately, still jet-lagged, we awoke at 5:30 the next morning and hit the road. The second wave of the blizzard was upon us, and I drove through the deep snow, often following snow-plow teams across I-80 from Jersey and through the Pocono’s mountains. Luckily, the farther west we got, the clearer the roads got, and we made it home at about the time the plane was pulling out of JFK (though we learned it left about 30 minutes late and we likely would have been stuck in Cincinnati another night). We made the right choice driving, and the adventure of a lifetime (start to finish) had come to an end.

Review of the Tour Companies

We originally booked a tour with Sarah Tours, but we eventually learned (after we arrived) that they subcontracted us to Relations Tours. First off, Mohammed Masrour ([email protected]) made this the trip of a lifetime. I can’t say enough for this kind, smart, and extremely eager to please man. His boss, Brahim Laaboussi of Relations Tours ([email protected]) was also on top of things. He met with us in person twice and was in constant contact with Mohammed, ensuring that all was well. Our experience with Sarah Tours was not nearly as good. The owner is located in the USA. This made him easy to approach before the trip, but impossible to reach during the trip.

We made our agreement in the beginning with the Sarah Tours operator that included full board. However, this tidbit was not conveyed to anyone in Morocco, and so we ended up paying for some of our meals. Full board on Sarah Tours ended up translating to full board at the hotel, where the cost could easily be charged to the tour company. We did our shopping day with a Sarah Tours guide, and not even he was told that our meals were included. We ended up at a relatively expensive (but ohh soo good!) restaurant, but had to pay.

However, I would recommend Salim as a Fes Medina guide without reservation. He hooked us up with true quality vendors. It was not the crap that abounds at the souk. However, be prepared to spend good money to get good quality.

While in Morocco, we didn’t hear from the Sarah Tours operator once. Fortunately, Brahim was in town representing his company. Overall, I’d recommend working with Relations Tours directly and cutting out the middle-man. They are good enough for Sarah Tours to subcontract to, and they gave us the experience of a lifetime on this trip. However, I have nothing against Sarah Tours because without them, I’d never have met Mohammed, and they made it easy to get to Morocco (though it’s not that hard if you want to try).

My Lady’s Tips for Morocco

Like many other Muslims that day, Mohammed brought home his sheep Friday morning and tied it up on his roof top (which, like many Moroccan houses, was an open floor atop the house having walls but no ceiling. Like the other sheep we’d seen, Mohammed’s was stubborn. Eventually the butcher showed up.

Mohammed and the butcher held the sheep down while the butcher made one swift slice through the neck, cutting open the windpipe and severing the two carotid arteries, which continued to pump blood from the body as the sheep fell to the ground and exhaled its last breath through its open neck. The head was removed and the body hung as the blood flowed from the severed arteries. The hide was slid from the body like pulling off a tight shirt, and the chest opened. The stomach was carefully detached and dropped to the floor so as not to damage the meat. The organs were put on a tray, along with some fat. Since the meat needed to be aged for a few more days, this was a day for eating organs and heads. Mohammed’s wife and her sister prepared some liver which was boiled then wrapped in fat and grilled on skewers. We tried some, but fortunately, we didn’t hear “you have to ate!” at that point. We walked the streets and saw people grilling sheep heads on open fires in celebration. Soon the children would be selling heads to make a few Dirham.

After this second climax of the trip, we drove to Casablanca, via the ancient Roman city of Volubulus, where we saw our first tour bus. We again counted our lucky stars that we picked the right tour, as we saw the fat oozing from this lady’s spandex. We were then off to Casablanca, where we spent a night at a hotel on the shore where we had dinner.

The hotel food had nothing on the home cookin’. We were so fortunate to be able to eat like real Moroccans. We woke up the following morning and snapped a few pictures at the large mosque in town. We were then escorted to the departure point by our guide after a near-teary goodbye.

Our flight back was uneventful (with better seats) until we hit the states. It turned out that the first major snowstorm of 2005 was brewing below us. Of course, we were left in the dark from the crew except that the weather was bad below, so we were going to circle for a while. On the way back, there was no movie on the screen, only the flight trajectory. We saw the plane circle the north-end of Long Island, followed by a circle at JFK. We were then informed that there was an “emergency landing” at JFK (euphemism for “a plane slid off the runway”), and that we were being diverted to Newark.

We landed in Newark and eventually got through customs there. I knew that nobody would be watching out for us and decided that our best option at that time was a drive back to Cleveland. Our flight from JFK to Cincinnati was cancelled, and the next one was not to leave JFK until the following day at 3pm. Due to the weather, the monorail was out of commission, so we waked with our luggage about a half-mile through foot-deep snow to Hertz. We hooked up with a Toyota Camry and I drove through the conditions until I couldn’t drive any more (this was about one hour, putting us just off of I-280 in Jersey at a Residence Inn). It was about 2:30 am Morocco time by the time I got to bed at 9:30. Fortunately, still jet-lagged, we awoke at 5:30 the next morning and hit the road. The second wave of the blizzard was upon us, and I drove through the deep snow, often following snow-plow teams across I-80 from Jersey and through the Pocono’s mountains. Luckily, the farther west we got, the clearer the roads got, and we made it home at about the time the plane was pulling out of JFK (though we learned it left about 30 minutes late and we likely would have been stuck in Cincinnati another night). We made the right choice driving, and the adventure of a lifetime (start to finish) had come to an end.

Review of the Tour Companies

We originally booked a tour with Sarah Tours, but we eventually learned (after we arrived) that they subcontracted us to Relations Tours. First off, Mohammed Masrour ([email protected]) made this the trip of a lifetime. I can’t say enough for this kind, smart, and extremely eager to please man. His boss, Brahim Laaboussi of Relations Tours ([email protected]) was also on top of things. He met with us in person twice and was in constant contact with Mohammed, ensuring that all was well. Our experience with Sarah Tours was not nearly as good. The owner is located in the USA. This made him easy to approach before the trip, but impossible to reach during the trip.

We made our agreement in the beginning with the Sarah Tours operator that included full board. However, this tidbit was not conveyed to anyone in Morocco, and so we ended up paying for some of our meals. Full board on Sarah Tours ended up translating to full board at the hotel, where the cost could easily be charged to the tour company. We did our shopping day with a Sarah Tours guide, and not even he was told that our meals were included. We ended up at a relatively expensive (but ohh soo good!) restaurant, but had to pay.

However, I would recommend Salim as a Fes Medina guide without reservation. He hooked us up with true quality vendors. It was not the crap that abounds at the souk. However, be prepared to spend good money to get good quality.

While in Morocco, we didn’t hear from the Sarah Tours operator once. Fortunately, Brahim was in town representing his company. Overall, I’d recommend working with Relations Tours directly and cutting out the middle-man. They are good enough for Sarah Tours to subcontract to, and they gave us the experience of a lifetime on this trip. However, I have nothing against Sarah Tours because without them, I’d never have met Mohammed, and they made it easy to get to Morocco (though it’s not that hard if you want to try).

My Lady’s Tips for Morocco

- Bring a French/English Dictionary

- Biodegradable camping T/P. Your bathroom may be a toilet with a bidet, a Turkish bath, or the great outdoors.

- Camping Towels

- Flashlight

- No headwear needed if you are worried about religious persecution

- If you travel in the winter, the homes have no heat

- When shopping, it is OK to say no and walk out. Walking out is the only way because as long as you are there, there will be constant sales pitch. Walking out helps negotiations.

- When bargaining, go less than half of the initial offer. The lower you start, the lower the final price.

- There are no double-sheets on most beds (except the 3-star hotels for the tourists). Consider a silk sleeping bag if this bothers you.

- You must ate! You must ate! It is the only way to make your Moroccan hosts happy.

- You should stick to bottled water. You also can attempt the pharmacist’s recommendation (that worked for us) of employing a daily regimen of 2-pepto tablets three to four times a day. However, Salads are often cooked, so no need to worry about that. Moroccans also peel their apples, so you’re fine there as well.

- Drink Tea. The sugar alone is enough to keep you going through the toughest moments of culture shock and constant movement of travel.

- Don’t go to Morocco if you are a diabetic, vegetarian, or on the Atkins diet.

- They don’t use washcloths.

Copyright © 2013 RED